NESKANTAGA — Living in third-world conditions for 30 years.

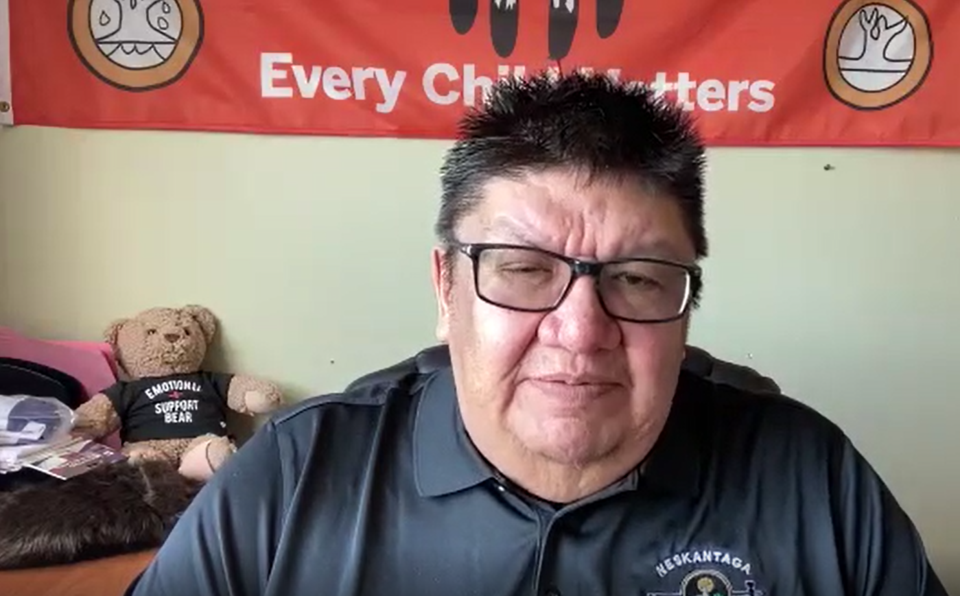

That’s how Neskantaga Chief Chris Moonias sums up what he and the members of his community have been dealing with for a generation without safe tap water.

The remote First Nation, located about 430 kilometres northeast of Thunder Bay, has now been under a boil water advisory for three decades almost to the day — the longest such time any community in Canada has gone without clean drinking water.

Moonias said not being able to trust the water that comes out of the taps for that length of time is traumatic.

“It has long term … mental health issues that are associated with this,” Moonias said during a press conference held over Zoom on Friday to mark, what a press release called, “a grim milestone.”

“Does the community deserve clean drinking water?” Moonias continued. “At some point in time, some people say maybe we're not considered humans to have clean drinking water.”

“Those are things that I hear from my community members.”

There have been numerous attempts to fix the existing water treatment plant over the years, along with commitments from government to build a new plant and end the water crisis, but work still continues on the existing facility with no real results, Moonias said.

“They've been working on this upgrade for a long time,” he said. “We call it a Frankenstein but it's something that has not happened and we continue to have issues with it and the people that are involved just can't seem to produce clean drinking water to our houses.”

The community has also had to evacuate due to the ongoing issues with the water supply: most recently in 2020 when an oily sheen was discovered on the surface of the water in the reservoir, and in 2019 when the plant’s pumps failed.

For those who call the community home, the mental and physical health effects are very real.

“I was just sitting with my great granddaughter at home during lunch hour and I was looking at her arm and I see rashes on her forearm,” Moonias said. “It's sad to see her go through that and it's sad to see our community members looking like this.”

“We've got governments that want to access our territories and to extract riches, and yet, we don't really benefit.”

Aside from being frustrated with how long it’s taking for Ottawa to come up with a permanent solution, Moonias said he’s also disappointed with the fate of Bill C-61, or the First Nations Clean Water Act — legislation that, if passed, would establish minimum national standards for drinking water and wastewater services in First Nations and strengthen funding commitments to provide those services.

It reached the report stage in the House of Commons, but the prorogation of Parliament and a looming federal election mean that the bill is effectively dead, Moonias said.

“We would have had standards for clean drinking water,” he said. “Right now, there's no standards for water in our community, or in any First Nations, and this bill would have put some standards so we don't fall below again.”

“I want to hear party leaders say that they'll continue to address the boil water advisories right across Canada — not only Neskantaga — and make sure that there is legislation put in place to protect our communities and our source water.”