EDITOR’S NOTE: This article originally appeared on The Trillium, a new Village Media website devoted exclusively to covering provincial politics at Queen’s Park.

With COVID-19 mostly in the rear-view mirror, Ontario wants to get a head start on preparing for the next pandemic.

Public Health Ontario (PHO) is looking to contract the Toronto-based company BlueDot to do global infectious disease monitoring by looking at vast swaths of data, from social media posts to livestock futures and more, for hints on when and where the next big outbreak will occur and how the province can respond.

BlueDot was started by Dr. Kamran Khan, a University of Toronto professor and clinician-scientist at St. Michael’s Hospital, in the aftermath of the SARS outbreak. The company made headlines in the early days of the COVID pandemic for raising alarm bells about a disease outbreak in Wuhan ahead of some governments and global public health organizations.

The company uses a mix of artificial intelligence and regular human intelligence to scour different sources of data to monitor potential disease outbreaks.

BlueDot did not respond to an interview request.

PHO put out a tender in February, announcing its intention to purchase the company’s services for one year, with the option to extend for another. It’s the first time PHO has ever done something like this, a PHO spokesperson told The Trillium.

“This tender is aimed at sourcing a solution that will enhance our ability to conduct real-time monitoring of key information sources to identify emerging health threats,” the spokesperson said in an email.

It’ll “strengthen preparedness and planning activities” to support the provincial government and local public health bodies.

It could be the first time a province has done something like this, the Public Health Agency of Canada told The Trillium.

“PHAC is not aware of other events-based surveillance systems similar to GPHIN in other provinces or territories. Many jurisdictions do conduct basic media monitoring for internal situational awareness,” a spokesperson said.

The tender is in the form of an advanced contract award notice. It’s a type of competitive procurement governments use on occasion when they already have a particular company in mind.

Instead of sole-sourcing BlueDot’s services from the jump, the government chose to give other interested companies a chance to bid if they could provide the same service. If no other company submitted a bid by the tender’s closing date, PHO had the green light to go ahead with BlueDot, which they intended to do, the spokesperson said.

The listing expired March 13, and the contract was originally supposed to start on April 1. As of April 6, the procurement process was still underway, PHO said.

Because the contract hasn’t been fully wrapped up, PHO doesn’t have an exact idea of how it’ll use the information it gathers to help other health-focused organizations within the province’s purview, like the Ministry of Health.

“We have not yet established processes that will be in place when it is up and running, though our goal would be to share any significant flags on global emerging issues or health threats with our ministry partners in a timely way,” the spokesperson said.

The Trillium asked Health Minister Sylvia Jones’ office what their plans were for sharing information with other provincial governments or the federal governments, but did not receive a response.

PHAC also does this kind of work through the Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN).

“GPHIN is Canada’s early warning and situational awareness system for potential public health threats worldwide; it operates by searching reports, media coverage, and other open sources of information for events that could pose a serious risk to public health,” a PHAC spokesperson told The Trillium.

Like BlueDot, GPHIN made headlines in the early days of the pandemic after a Globe and Mail investigation revealed one of the program’s key features — lauded in global public health circles for decades — had been “effectively switched off.”

GPHIN is credited with early detection of swine flu (H1N1), the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and Ebola, helping other countries prepare. In 2019, the Globe investigation found, the program diverted resources away from international monitoring to focus on domestic threats.

The reporting led to an auditor general report and an independent review of GPHIN’s past and future. The review and PHAC’s comments to The Trillium dispute the Globe’s conclusion that GPHIN was “effectively switched off” and caused a delayed pandemic response in Canada.

GPHIN makes its findings available to “Canadian public health practitioners working in the health sector, including those working in the provinces and territories.”

PHAC also “regularly” shares “information of mutual interest” with PHO and other provincial health organizations. The two organizations haven’t talked about PHO’s latest move into the space, PHAC told The Trillium in March.

Given PHAC already does a lot of this work, the whole effort is a bit puzzling to Queen’s University professor David Skillicorn.

Skillicorn is a professor of mathematics and computer science and is working on developing a similar outbreak monitoring system in Australia.

“Health is a provincial responsibility, but on the other hand, the kinds of health emergencies that they're looking for would not generally be bounded by provincial boundaries,” he said.

He raised several other technical issues stemming from the GPHIN ordeal and the lessons learned, or lessons that should’ve been learned.

“One of the problems in this area is that we really don’t know how to do it yet,” he said.

GPHIN was fairly low-tech, he said.

“What GPHIN was doing was basically subscribing to Factiva, and reading relevant stories and having meetings to decide” whether to send out warnings.

“If you want it to move up to high-tech stuff, we actually didn't know a whole lot about how to do that,” which is one of the things he’s working with the Australians on, he said.

Skillicorn didn’t criticize the company. Instead, he said he’d like to see the government try to expand on existing platforms like the Acute Care Enhanced Surveillance (ACES) system.

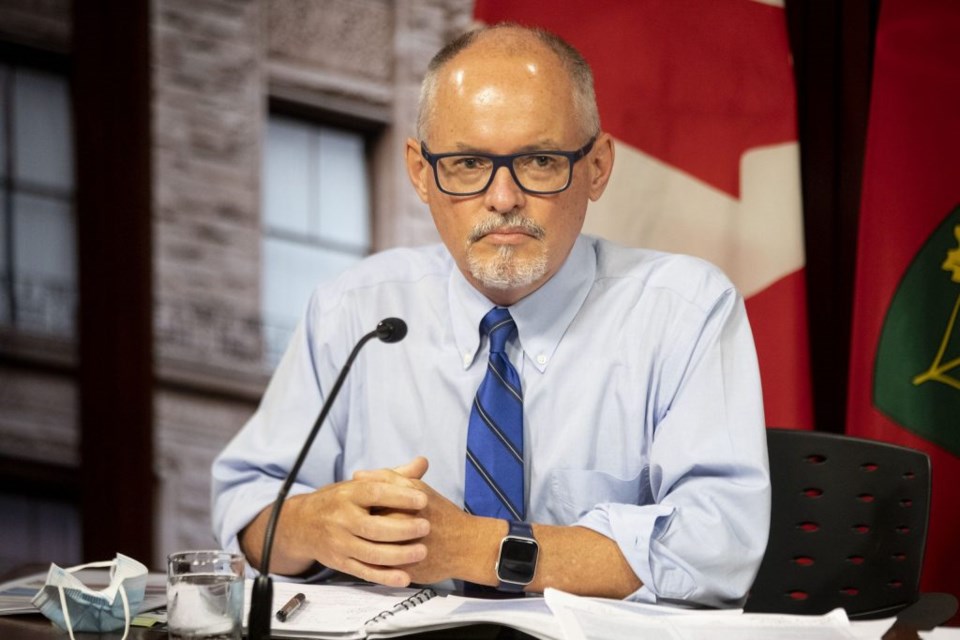

ACES monitors emergency department visits and admissions to hospitals from nearly all acute care hospitals in the province to provide early warnings, similar to what companies like BlueDot do using different data sources. It was started by Dr. Kieran Moore, now Ontario’s chief public health officer, in 2004.

“Ontario is really quite well positioned to do a data-driven kind of health warning dashboard system. But that doesn't seem to be the direction that this particular provincial government is heading in,” he said.

The Trillium asked Jones’ office about this specific critique, but did not receive a response.